Hops are as important to beer as grapes are to wine. New hybrids are entering the picture every year, changing what a beer is able to do in terms of flavor and fragrance. From a beer-making standpoint, one major consideration is whether to go the wet hop or dry hop route. But the names can cause a little confusion.

For the record, most hops are dried. They get picked in the field, treated to some warm air, and are often shaped into pellet-like cones for use later on. Since most are grown in the northwest but beer is made all over, this is a great way to preserve a good hop and ship it all over the globe. It’s said that they can last for several years in this format (although we all know how great a fresh-hop beer is).

But a dry-hopped beer usually refers to the actual beer-making approach. Hops are added later in the process so that they hang on to their aromatic intensity. Part of that intensity is owed to the fact that dried hops tend to be denser in terms of the flavor and fragrance punch that they pack. The overall IBU dial will be adjusted, too, as hops inject varying amounts of bitterness. There are even double dry-hopped beers, which means if triple and quadruple dry-hopped beers don’t exist yet, they’re coming soon.

You’d think wet hop would be just the opposite — throwing the flavorful cones in during the boil, giving them a good soak. Nope. A wet-hopped beer is a lot like a fresh-hop beer. It’s made with hops that are not air or kiln-dried. They tend to be moist and full of flavorful oils, having just recently been harvested. The flavors tend to be more nuanced and green in nature. And if it weren’t for new hop oils and extracts, you’d really only find wet-hop beers once a year, right around the hop harvest in early autumn.

Some breweries will do a wet and dry take on the same beer, but I’ve yet to see both versions canned or bottled and available side-by-side. Often times, the wet or fresh hop version is a limited run and simply poured on draft at the brewery’s headquarters. Either way, it’s worth looking out for when sipping beer in the fall.

Here are some worth trying to see what side of the hop fence your taste resides.

Wet: Great Divide Fresh Hop Pale

This beer from Denver’s Great Divide sums up the fresh hop effect. It’s citrusy and piny, with a bit of that mowed-grass dankness that’s so strangely satisfying.

Wet: Surly Wet Hop

This beer from Twin Cities brewery Surly is alive and kicking. The hop bill changes annually but the beer itself is reliably raw yet approachable.

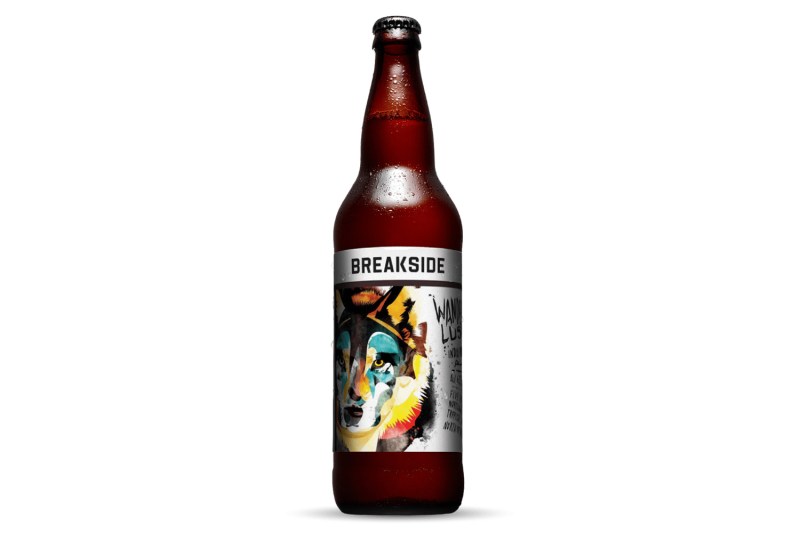

Dry: Breakside Wanderlust

Portland’s Breakside has been turning out some of the best IPAs around for years now. The Wanderlust is a golden IPA made with a handful of different hops and shows earthy, herbal, and grapefruit flavors.

Dry: Fort George Three-Way IPA

Fort George’s annual collaboration beer has become legendary. It reflects the power of meticulous hop combinations and the ability of a well-engineered dry-hopped beer to taste so fresh you’d think it was wet.

Wet: Sierra Nevada Southern Hemisphere IPA

Ah yes, the other half of the globe. It affords us a second opportunity to brew wet-hop beers, thanks to seedy transit! This one from iconic brewery Sierra Nevada is made from hops grown in Australia and New Zealand and is divinely fruity and tropical.