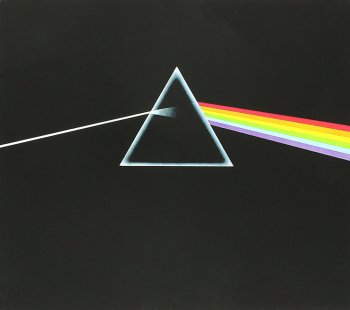

Few records in music have attained the legendary heights of Dark Side of the Moon. Pink Floyd’s heady triumph has become its own brand, with an aesthetic that extends beyond its foundation of progressive rock. The name alone immediately conjures up the prism cover art, which has been slapped on everything from bumper stickers and t-shirts to blacklight posters and even automobiles.

Yes, the album syncs up frighteningly well with the beginning of The Wizard of Oz (unintentionally, the band says). But it’s also a masterpiece musically, combining innovative sounds with production finesse that was way ahead of its time. The result is a record that plays fluidly from start to finish, influenced by experimental rock, blues, jazz, and artistic studio expressionism.

The band was well-known by the ’70s. Members gathered around a concept album approach, a grouping of songs revolving around a more direct and cohesive theme. The then-recent departure of founding member Syd Barrett and his mental struggles, along with the exhausting act of being a prominent rock band in the heyday of the classic rock era, had Pink Floyd thinking about madness. Instead of writing spacey or analogous tracks, the band would look things like greed, death, and insanity dead in the eye.

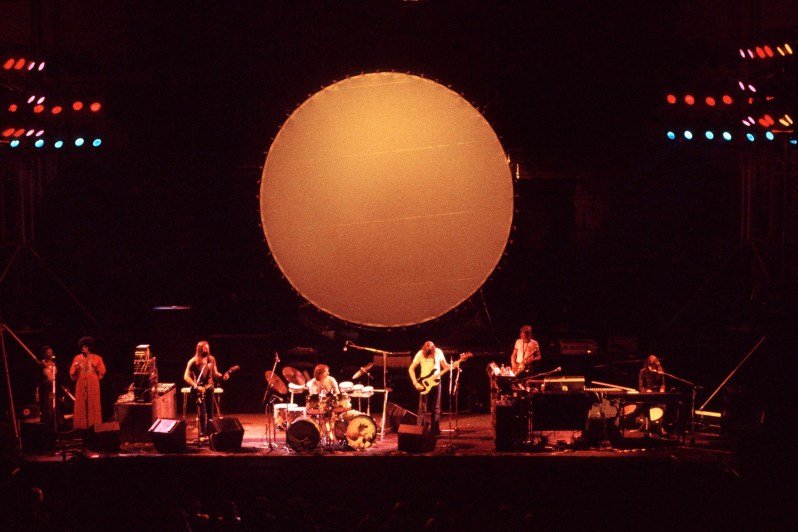

Interestingly, the album was originally intended to be something Pink Floyd would play in its entirety and lug around as a single touring item. Initially dubbed Dark Side of the Moon: A Piece for Assorted Lunatics, it was to involve tons of extra live stage gear, like a PA system and a 28-track mixing desk. Ultimately, it made its way to Abbey Road Studios where Alan Parsons helped release it to the world.

The layering of samples and effects is impressive even now, almost fifty years later. Keep in mind that in ’73, stacking recordings like this was exhausting and all done to tape, sometimes with the use of multiple mixers operating simultaneously. The album beautifully weaves in everything from field recordings to flashcard responses from studio staff (most famously, “Why should I be frightened of dying?” at the beginning of “The Great Gig in the Sky”). Equally entertaining is the legend that Roger Waters would skip out on sessions to watch his favorite soccer team Arsenal and that the band would sometimes prefer Monty Python over playing.

A living, walking animal, the album begins with a fitting heartbeat sample (and ends that way, too), which spills organically into the wave-like first electric guitar chord of “Speak to Me.” At this point, the listener is already underwater, in a sea of whale song that’s resonant and weirdly reassuring.

By “On The Run,” conditions are growing eerie. The listener feels as though he’s entering the darkness of the psyche, with droning sounds intertwined with maniacal laughter and a huge degree of tension. “Time” possesses an intro any band would kill for, with a gorgeous uprising arc capped by excellent, measured percussion. The song demonstrates great vocal interplay between David Gilmour and Richard Wright and Zeppelin-esque guitar work.

Then, “The Great Gig in the Sky,” the hardest song on the planet to cover via karaoke. It features session vocalist Clare Torry going absolutely bonkers, a free-verse-meets-gospel sort of vocal journey that’s impossible to replicate. The story goes that she apologized for its intensity after the recording session only to be showered with praise by the band. Her vocals ebb and flow like the tide itself during this ocean of a song.

“Money” is sinister and bluesy, reminding us of the perils that come with currency. The bass line from Roger Waters alone is famous. Throw in neat samples of coins and cash registers and you’ve got the backbone to hip-hop before the genre even existed. The record then sways along via “Us and Them,” a touching, anthemic song bolstered by synths, brass, and big background vocals. Like a tortured genius, the song exudes both potential and a sense of dread, scampering toward either end of the spectrum but always returning to Gilmour’s calming vocals.

The song segues cleanly into “Any Colour You Like” — so much so it’s easy to forget they’re two separate tracks. While there’s a fair amount of jamming throughout the album, it’s kept pretty buttoned-up to this point. Here, they let loose, playing something you’d expect more from a basement in the wee hours than a famous recording studio.

The final two blows dealt by “Brain Damage” and “Eclipse” serve as the perfect climactic finale for the album. Craziness has seeped in and, with the latter song especially, there’s a feel of submission. It’s a swelling, sonic reminder that we’re oh so small in the overall scheme of things and that all of these dualities (life/death, creation/destruction, buying/stealing) are silly tidbits beneath the dual force of them all, the sun and the moon.

Strangely, it’s not the only 42-minute sonic block worth diving head-first into from 1973. Even more strangely, Dark Side of the Moon seems to grow more relatable with each coming year. Because it deals in the always on-topic subject of coping with the modern world, the record may be even better, somehow, another fifty years from now. As robots take over, digital technology spans the horizon, and cars begin to drive themselves, this monumental rock album will continue to be the soundtrack of us all going mad.