The first time I look at any book of photography, I flip through every page at a quick pace to get a sense of the content, taking more time to linger with and absorb certain images on subsequent look-throughs. So it was with Jonathan Brand’s Lower East and Upper West: New York City Photographs 1957-1968

But within a few quick turns of the page, I found myself arrested by the gaze of middle-aged man with dark skin and a kind, weathered face. As his picture was taken in the course of the work day, he wears a soiled apron and heavy gloves yet he exudes a sense of refinement and poise. The picture is a snapshot, technically, as are most of the images in this collection — Brand often didn’t even raise the viewfinder to his eye, in fact, shooting on the go — yet it manages to feel more like a portrait than a fleeting moment. This is partially because of the face of the subject, and partially because of the framing, which is a textbook example of the rule of thirds. But the reason this and so many of the other pictures in the book work so well is simple: looking at everyday life is fascinating if your eyes are actually open.

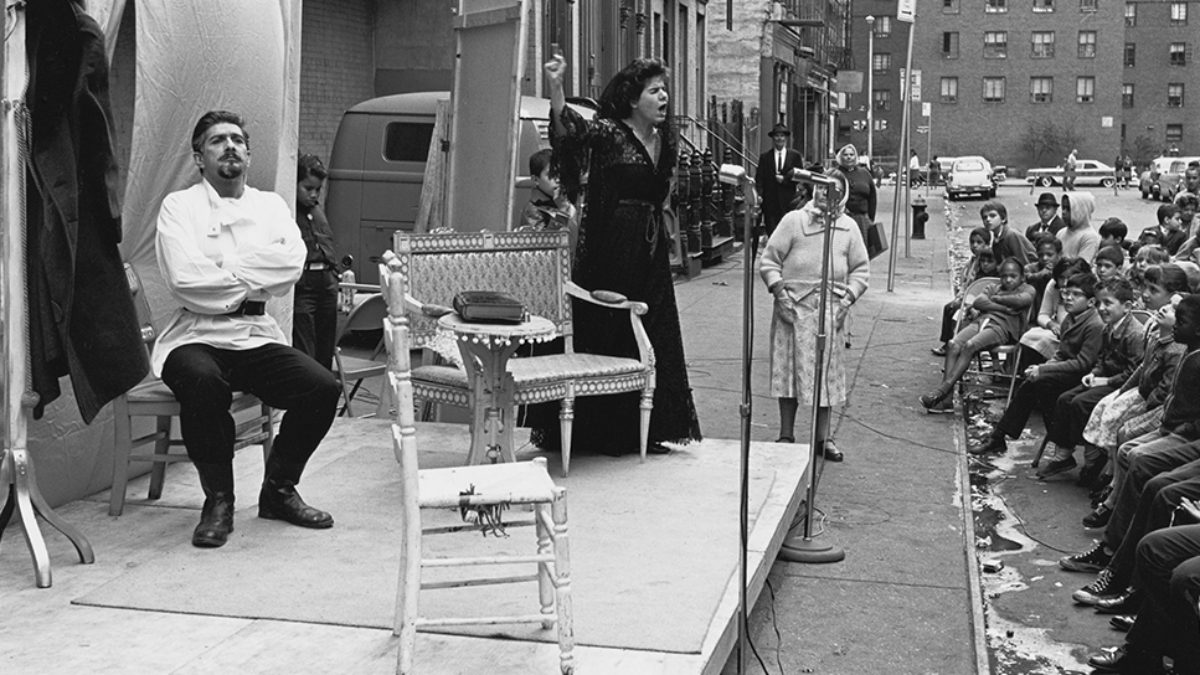

Lower East and Upper West captures a remarkable decade in New York City history. In many ways, the period spanning from the late 1950s to the late 1960s bridged the gap between the “old days” and the modern. In this book we find images of a horse-drawn carriage from which a man hawks onions at 10 cents for three pounds, but we also see stylishly-dressed 20-somethings who would not look out of place strolling through 21st century Manhattan. There are old men wearing newsboy caps and young men wearing Wayfarers. Brand’s pictures capture a post-war city that’s also pre-1970s and ’80s crime wave. The city here doesn’t look clean and quaint, but it’s not a teeming mess, either.

One of the things that struck me most about Brand’s street photography was how often he involved the subjects in the process. While there are plenty of images captured in which those pictured are unaware of the lens and are often in the middle off an action, quite often the subjects are looking right at the camera as if having been asked to pause for a moment and hold still. It’s almost the antithesis of Henri Cartier-Bresson’s “decisive moment” approach to photography. You can picture Jonathan Brand strolling along Sixth Avenue (or 82nd or Park Ave or what have you) and stopping a passerby to raise a Leica for a quick snap then thanking them and hurrying on toward his job at the advertising agency (he worked as a copywriter and director of an ad agency for many years, FYI).

In short, we feel almost like we are interrupting these people when we look at their pictures. When we flip away, the children can get back to dancing, the elderly couple can resume their chat, and the workmen can go on with loading the truck.

When we close the cover of Lower East and Upper West, one can imagine that this bygone New York City, a city that feels distant enough for nostalgia but close enough for familiarity, gets right back into the swing of things. We might have interrupted it for a moment, but no one seems to mind that much.