You can hear the whine of the engines from several miles away. From the expansive grassy field near the track, the whine grows to a howl. You step out of your car and approach Lime Rock Park with a growing sense of excitement and nervousness; the power of the vehicles you will soon see becomes all the more clear as the decibels increase. Finally, as you cross the bridge into the area ringed by the racetrack, the cars will almost invariably rush by below you, and now the howl is a deafening roar; you can’t even hear yourself think, but if you could, your thoughts might be something along the lines of this: holy shit.

Cars will almost invariably pass below you while you cross one of the two bridges leading into the heart of Lime Rock Park because the track is just 1.5 miles long, which means most race cars complete a circuit in about one minute. Lime Rock is one of the shortest tracks on the professional IMSA Grand Prix circuit (that’s International Motor Sports Association, FYI), but most drivers and fans see this as an asset, not an issue: it means tighter turns, explosive straightaways, and more technical challenges for the men and women behind the wheels of some of the fastest automobiles on earth.

Lime Rock Park was opened in 1957 and the track layout has not changed in the six decades since it first saw use. In its standard configuration, the track requires a driver to complete seven turns per circuit. The current record for a single lap is a hair over 43 seconds. (1.5 mile track… 43 second lap. If you do the math, you’ll see that it equals fast.) Lime Rock is the oldest continuously operating race track in America, and is the third oldest overall (there’s a track in Wisconsin that dates from 1955 and one in California from the same year as Lime Rock). Today, it is the site of many of the world’s major auto racing events, such as the IMSA WeatherTech SportsCar Championship Grand Prix event I recently attended.

On the drive up to the race (for the record, I was driving a blue Ferrari 488 Spider that was mine for the weekend — it was superlative), my knowledge of auto racing was essentially limited to what I’d researched in the preceding two weeks when the opportunity to attend the event arose. By the end of the weekend, I’d learned a fair amount more about auto racing, including two very important takeaway points: First, I now have a much better understanding of why people like professional racing, which in a nutshell is because it is undeniably compelling to watch. And hear. (For the record I don’t mean stock cars on a huge ovular track. That remains arcane to me.) Second, I now know that when you go to a race, you should bring hearing protection.

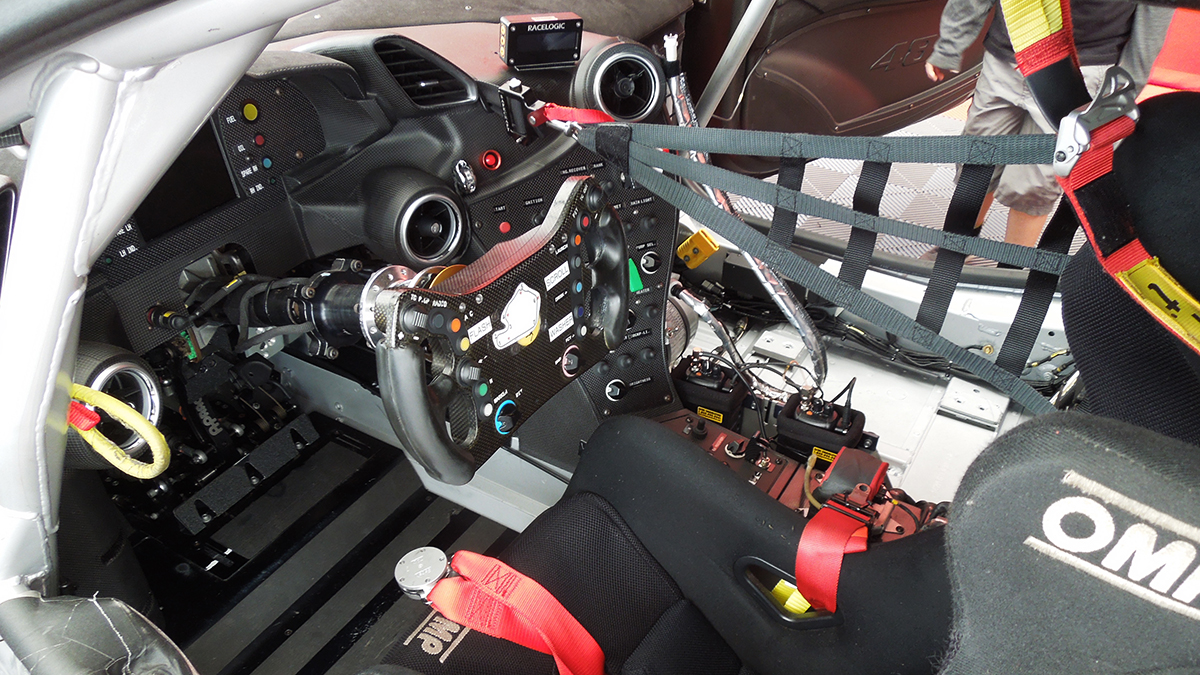

Prior to the race, I had the opportunity to spend time in the paddock of the Scuderia Corsa racing team, meeting their celebrated driver Christina Nielsen a few hours before she climbed into her Ferrari 488 GTE (she would split the driving with her teammate Alessandro Balzan) and sticking my head into a race car that would soon be screaming around the track at speeds faster than most of us will ever approach when not in flight.

The inside of a race car looks more like the cabin of a space vehicle than it does to the interior of the car in your driveway. From wires and tubes to strange buttons and levers to the reinforced cage built around the driver’s seat, these things are intimidating in their complexity and in the clear power waiting to be tapped as the vehicle sits at rest. How much power are we talking about? Well, the car I drove up in has a standard 660 horsepower. Yeah.

Amazingly, as it turns out, the Ferrari 488 has too much horsepower for the race in question; its abilities must be limited in order to bring the vehicle down to match the stated specifications all competing cars have to meet. But don’t worry, it’s still very fast. And loud. As are the other

After the start of the race, I spent time near several of the tightest curves — which have names like Big Bend, Righthander, and West Bend — and when a pack of GTLM (GT Le Mans) race cars speeds by at about a hundred feet away from you, it’s breathtaking. I mean that almost literally. The engines certainly drown out all other sound. Even from the middle of the multi-acre area ringed by the track, where you can find concessions, retail, restrooms, hundreds of classic and modern

As the race lasts more than two and a half hours, I had ample time to wander around the interior of the track, to stop back by the racing paddocks, and to visit several of the hospitality areas set aside for people who either bought or lucked into exclusive passes. (I was in the latter column.) At a Grand Prix race, you will see people dressed in their finest, with jacket and tie and martini in hand, and you will see people sans shirt or shoes sipping from cans with coozies. And everyone looks right at home. There are groups of grown men shouting and swearing and gaggles of kids playing and laughing. There are vintage cars lined up beside modified modern street racers. There is, to cut to the chase, a broad swath of Americana on display, but again, everyone looks to be right where they belong. A prevailing sense of camaraderie and cheer defines the mood whether you are right there by the track as the

Seeing as my son had inadvertently dropped my phone in a toilet the day before I left for the race, I was strangely untethered while attending the Northeast Grand Prix at Lime Rock Park. Once separated from the group with whom I’d attended the event — a mix of other writers and reps from Ferrari — I was on my own in what should have been a strange environment, but yet it felt like a generally warm and welcoming place. Everyone wanted to be where the were, and to share the experience of the race and racing culture with others.

Though I must admit I was far from disheartened when I left the park. After all, I did so in a Ferrari 488 that was still mine to enjoy for another 48 hours. And unlike the cars back on the racetrack, my ride was a convertible.