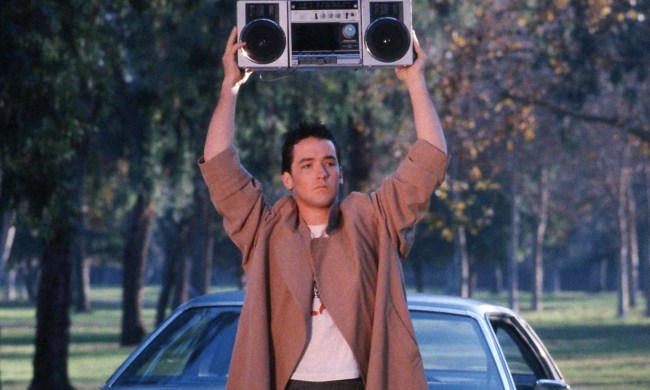

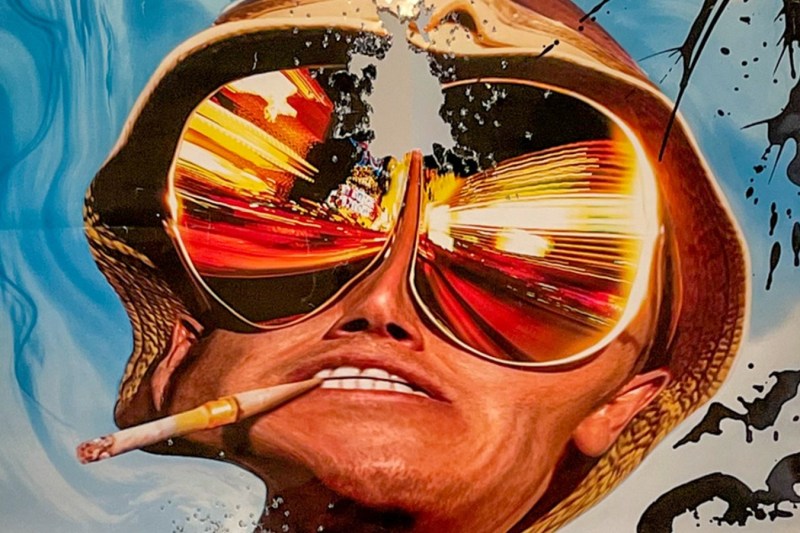

The first time I watched Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas also happened to be, appropriately, the first time I took LSD. At some point, I found myself wandering the shelves in the local Video Depot when a VHS cover jumped out at me. It showed a warped head with massive bug-eyed sunglasses — a sort of Dali-esque portrait — and without knowing much about the title, I nevertheless knew that this was the film I wanted to watch. I have no memory of how I actually got the tape out of the place as I cannot imagine they would have rented it to me, so twisted and incapable, which was due to my psychedelic condition.

Let me tell you: That moderate box-office bomb of a film that today has middling Rotten Tomato scores changed my life, as it did for so many aspiring writers, political junkies, and weirdos back in the day. At the time, the movie was generally considered a failure, but from the vantage of 2023 — 25 years later — it’s hard not to recognize the enormity of its impact.

Fear and Loathing in Hollywood

The film left an indelible mark on moviemaking on a pragmatic, industrial level. The stacked Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas cast helped establish the eccentric shape-shiftability of Johnny Depp and Benicio del Toro, and renowned director Terry Gilliam’s stylized, hallucinated aesthetic can subsequently be seen in everything from small independent films like Good Times to the blockbusters of the MCU.

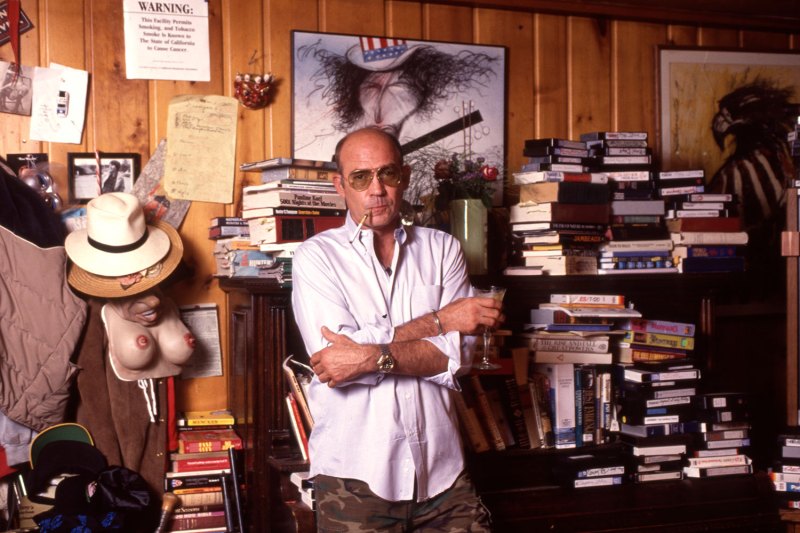

Beyond that, the movie reintroduced a new generation to its source material, the novel by Hunter S. Thompson. Thompson’s “gonzo” writing, an approach to journalism defined by its disregard of claims of objectivity and use of first-person narrative, had provided wildness to the journalistic and cultural ethos. By the late 1990s, his visibility was waning. Then all of a sudden, in the 2000s, thanks largely to the Fear and Loathing film adaptation, young journalists and writers began once again to borrow from the gonzo mindset.

The timeliness of ‘Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas’

The book Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas was very much a product of its time: the downfall of 1960s idealism, the corruption of the Nixon administration, the Vietnam War, and psychedelic paranoia — all of these went into the book and made it relevant to readers of the early 1970s. But by the 1990s, psychedelic drugs had been pushed firmly underground, large-scale war seemed a thing of the past, the Reagan/Bush/Clinton governments were by and large considered at least tolerably terrible, and the 1990s had been a relatively prosperous decade. Thompson’s frenetic calls to resistance simply didn’t find as eager an audience.

Within five to 10 years of the movie’s 1998 release, however, that had all changed. War, economic downturn, and general enmity toward the second Bush administration had taken hold. At the same time, psychedelic research and recreation were on the rise. And then Thompson released his final book, Kingdom of Fear, which tackled the rise of repression he saw post-9/11.

It was amid all of this that millennials — now largely graduating from school and entering into various professional fields — began reappraising Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas.

From the vantage of today — when weed is legal or on its way there in states across the U.S., with psychedelics close behind — to watch Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas is to dip into a work that is both artifact and instigator. It’s an artifact of a different time, when drugs were at best laughed at and at worst harshly punished. At the same time, it helped to instigate and inspire the activists, artists, scientists, doctors, politicians, and general gonzo aficionados who have helped shape the world we have today.

How does it hold up?

Rewatched (or first watched) from the perspective of 2023, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas is a better film than its 50% Rotten Tomatoes score would suggest.

The special effects still look outright fantastic. Its visual conveyance of a particularly ludicrous psychedelic experience is the most accurate you’ll see in any film ever in terms of the hallucinatory aspect. The whole movie is a feast for the eyes.

And the acting is similarly enjoyable. And this is all due respect to Bill Murray’s depiction of Thompson in 1980’s Where the Buffalo Roam, but Johnny Depp has forever set the standard for the true depiction of Gonzo — a 100% full-tilt, wild and weird, disturbingly believable gibbering maniac. Benicio del Toro is similarly tremendous in the sidekick role as Thompson’s drug-crazed attorney.

There are three common criticisms of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas: that its story is meandering, some scenes drawn from the book are perhaps superfluous, and it lacks much of the thematic punch delivered by the original text. These points are all accurate to some extent, though how much it will bother you is rather subjective. If the novel was a parable of sorts, then the movie is an amusement park funhouse. One doesn’t ride Space Mountain looking for Shakespeare.

I think my biggest issue with the movie from the here and now of 2023 involves its portrayal of drugs, psychedelics in particular. These days, our culture has begun to move away from the “crazy” conception of psychedelics. While there certainly is still a Dionysian element to the whole thing — particularly at festivals — it doesn’t fit as neatly into our current drug discourse as it did back in the late 1990s, when the War on Drugs was raging, and there was something revolutionary about pushing them to the extreme. Now the government has more or less begun to admit that the war is over, or at least drawing down, and the LSD-frenzied lunatic routine comes off somewhat dated.

So how does it hold up? While it definitely has throwback vibes, it’s still a fun ride with inconsistent intelligence along the way. The structural problems are balanced out by the eye-candy visuals and delightful performances, and what it lacks in thematic depth, it makes up for in enthusiasm for the source material and a fun viewing experience.

Not everybody is going to enjoy it, and some will be outright baffled by it, but Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas wasn’t a film made for everyone in the first place. More than anything, it’s something of a cultural meeting place for a certain set of weirdos. If you are among their ranks, you will likely find it a worthwhile watch.