From the outside, monthly vinyl subscription service Magnolia Record Club (MRC) doesn’t look like much. In an old industrial neighborhood that Nashville forgot, the window of its street-level door tells you no, go around, down, to where the back corner of the building and parking lot meet. It’s here, in a low-ceilinged room of whitewashed cinderblock, that I meet Paul Roper.

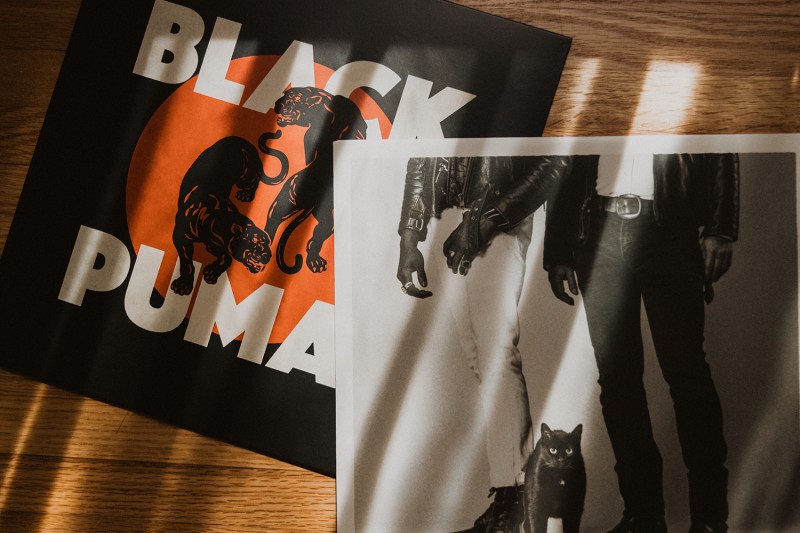

Roper, 42, is the president of Dualtone Records, which purchased MRC from its founder, musician Drew Holcomb, in 2018. Clean-shaven, with horn-rim glasses under a ball cap and a short-sleeve button-up over jeans, Roper leads us through a room honeycombed with large rolling postal bins empty and waiting for the next release to ship. The second, inner room is homier: Two seating areas with couches, throw pillows, coffee tables, and, of course, turntables. It’s here where MRC invites artists who, in addition to partnering with the company to produce special-edition pressings in a kaleidoscope of colors, may even sign a few. Dolly Parton (pink with red swirls), Wilco (ivory white), Willie Nelson (cerulean blue), Joseph (aqua wave), Brandi Carlile (ruby red), the War on Drugs (purple), Manchester Orchestra (aqua smoke); there’s seemingly not a band or artist played on AAA radio that hasn’t negotiated an MRC rainbow release.

Related Guides

Sitting down, Roper is quick to credit Holcomb, who launched the subscription service in 2015, for his vision: “If you look at the following of Dualtone versus the following of [Holcomb] — or the Lumineers, or any of our big bands — their followings are going to be 10 times what ours are, even though we’re running a successful business,” he says. “And it’s easier for an artist, who people are naturally following and fans of, to say, ‘You’re going to want to know records that I’m into and follow along with what I’m doing.’”

Holcomb was all about the personal touch, turning his fanbase on to both big and small records that he himself was vibing on. And it makes sense: If you’re into an artist, then that artist’s favorite artist is probably something you’d also dig.

But Holcomb was more than a tastemaker, he was also a soothsayer: Vinyl, already big in 2015, has only grown more popular in subsequent years. In 2020, records accounted for more than a quarter of all album sales and almost half of all physical album sales. On the opposite end of the spectrum, a new song is uploaded to Spotify every second, or around 60,000 each day. It’s a paradox: Despite the fact that more music is available than at any other point in history, there’s a growing need for someone to separate the wheat from the chaff. Holcomb built an effective threshing fork, and Dualtone bought it from him.

“People want something that’s curated,” Roper says. “That’s really what the club has become: This trusted filter for music fans.”

It’s not just the big artists and their new releases. Holcomb also started — and under Dualtone, it has extended — an “Artist Discovery” add-on, in which subscribers could receive an additional LP from an artist of whom they’d never heard. Recently, it was Cereus Bright’s Give Me Time on a special-edition silver-and-black splatter vinyl. “[Bright frontman Tyler Anthony is] a pretty unknown artist,” Roper says, shrugging, “but we just loved the record.”

But Dualtone’s MRC isn’t just resting on the well-established laurels of Holcomb’s startup. If anything, under Roper, the company has expanded on the MRC motto of “Curated by Artists,” tapping not only the artists themselves for special pressings and signings, but the artists in those artists’ orbits to provide context. Want to read Rayland Baxter’s thoughts on the Lumineers? Brandi Carlile’s musings on Maggie Rogers? It’s there, for the first time. Like the Players’ Tribune for sports or Inside the Actors Studio for cinema, Magnolia Record Club has created one of the most exclusive platforms for musicians, and one of the most inclusive platforms for their fans.

Subscriptions, to say the least, are up.

While Roper demurs when pressed for numbers, “We’ve seen it explode during the pandemic,” he says. Locked in their homes and apartments, audiophiles are reaching out for a different experience with their favorite music. Sometimes it’s just for the aesthetic: Records neatly stacked on a shelf, “a visual identity of musical taste,” as he calls them. After all, “You don’t pull out your phone and show your playlist,” he says. In company-wide discussion, employees openly debate a Golden Ticket-like concept, inserting the featured band’s favorite record in place of its own, just to see what percentage of MRC subscribers catch it.

But many more over the COVID-19 months seem to have found solace in the warm sound and distinct crackle of needles dropping into the grooves. “The thing about music, great art, great songs, is we’re tapping into the human experience and helping us understand and contextualize what we’re living in real time,” Roper continues. “Great music can be that salve for people. With vinyl, people are wanting a tactile experience that’s going to connect them to something outside of their reality that they’re living.”

A new generation is falling in love with records for the first time. Of the demographics Roper shares, MRC’s average subscriber is in his or her mid-30s, which means that when he or she was born, cassettes were the dominant audio medium, with CDs soon to take prominence. There’s a lot of catching up to do — and indeed, since our conversation, Amazon launched a subscription vinyl service with the aim of selling records from the “Golden Age of Vinyl” in the 1960s.

From Roper’s perspective, the rebirth of the format is good not just for his company specifically but for a beleaguered music industry at large. “I just hope that fans of music are realizing that there’s more to the process than just streaming one song from an artist through white earbuds,” he says. “The sonic quality, the experience of really getting to know an album and an artist through the [vinyl] process is what I hope the younger generation is experiencing through this — and that they don’t miss.”

Rather than singular songs, it’s records, the stringing together of tracks into an artistic statement, he says, that matter.

It’s a record you play on repeat to carry you through a breakup. And it’s a record you put on when inviting someone over for dinner and sharing a bottle of wine. In grief and love and joy, and when under stress, it’s records that you remember, and when you remember a record, you’re more likely to follow an artist over the long haul.

“[Dualtone] was about trying to create art and an album that’s timeless, that’s going to stand up 20, 30 years from now. Somebody’s going to put on a record and listen to it one through 10, one through 12.” Roper says. “That’s what we’re trying to build the Club on. That’s why we’re pressing albums.”