Back in art school, a bunch of us would hang out in the English department’s office, talking writers. Faulkner, Hemingway, Kerouac, Fitzgerald, all the big ones, along with neo-Western writer Cormac McCarthy. We loved McCarthy, who, a friend summed up, had the central philosophy that terrible, violent, and cruel things happen without any reason. The vindictive, inevitable Anton Chigurh from No Country for Old Men; the dispassionate torture in All the Pretty Horses; the drawn-out starvation and constant movement of The Road; the near-endless death and mutilation in Blood Meridian. We especially loved Blood Meridian, a book of nightmare journeys in the American West. From his home somewhere near Santa Fe, N.M., McCarthy releases his stories of despair to roam the country like monsters, fascinating college writing students and New York Times best-seller lists alike.

Related Guides

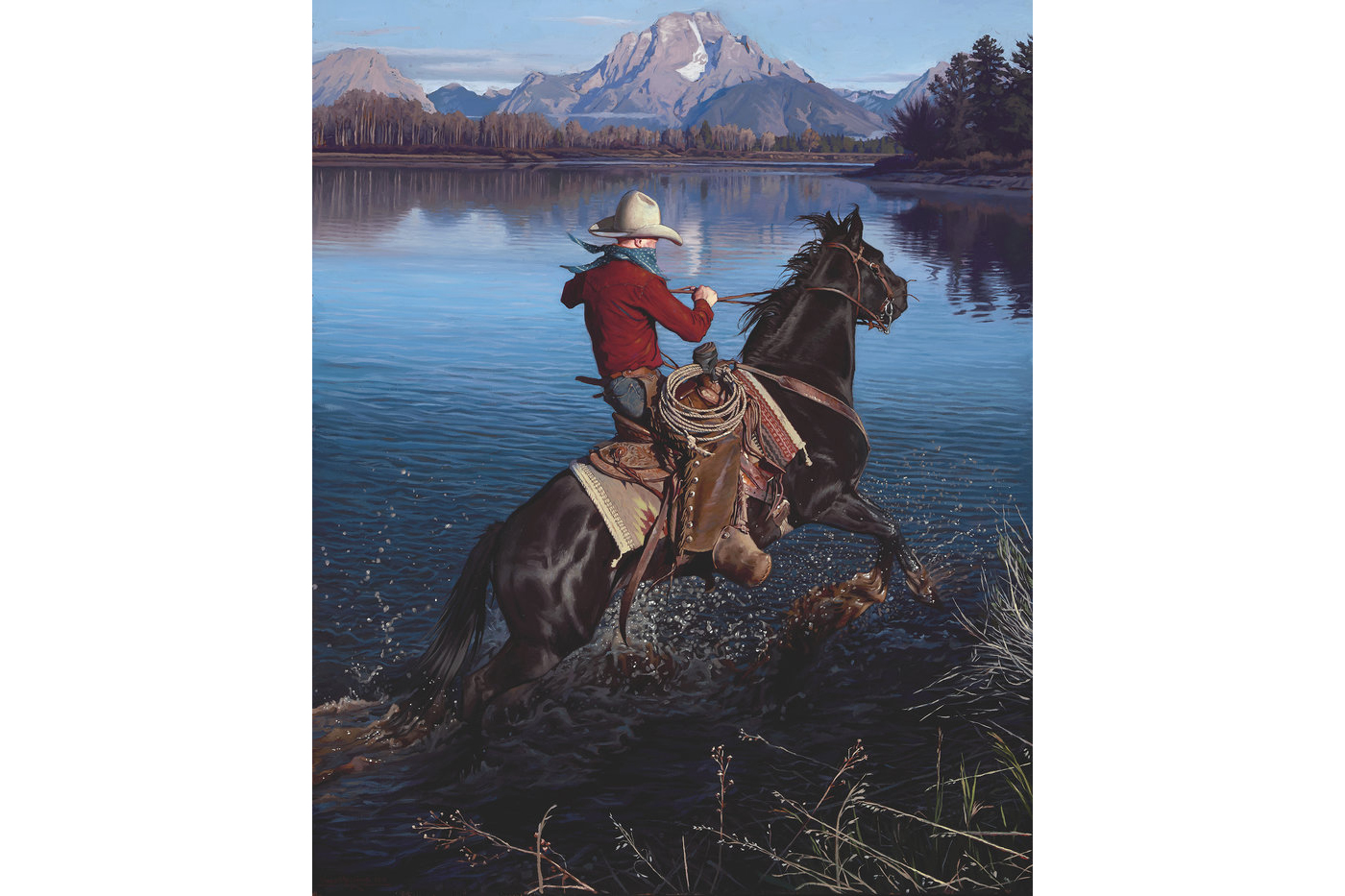

“I’ve read McCarthy, every single book. But that’s not what I want to paint,” Mark Maggiori tells The Manual. “When my daughter comes to see my paintings, I want to tell her a story. I don’t want to hide the truth; I want to tell her a better one.”

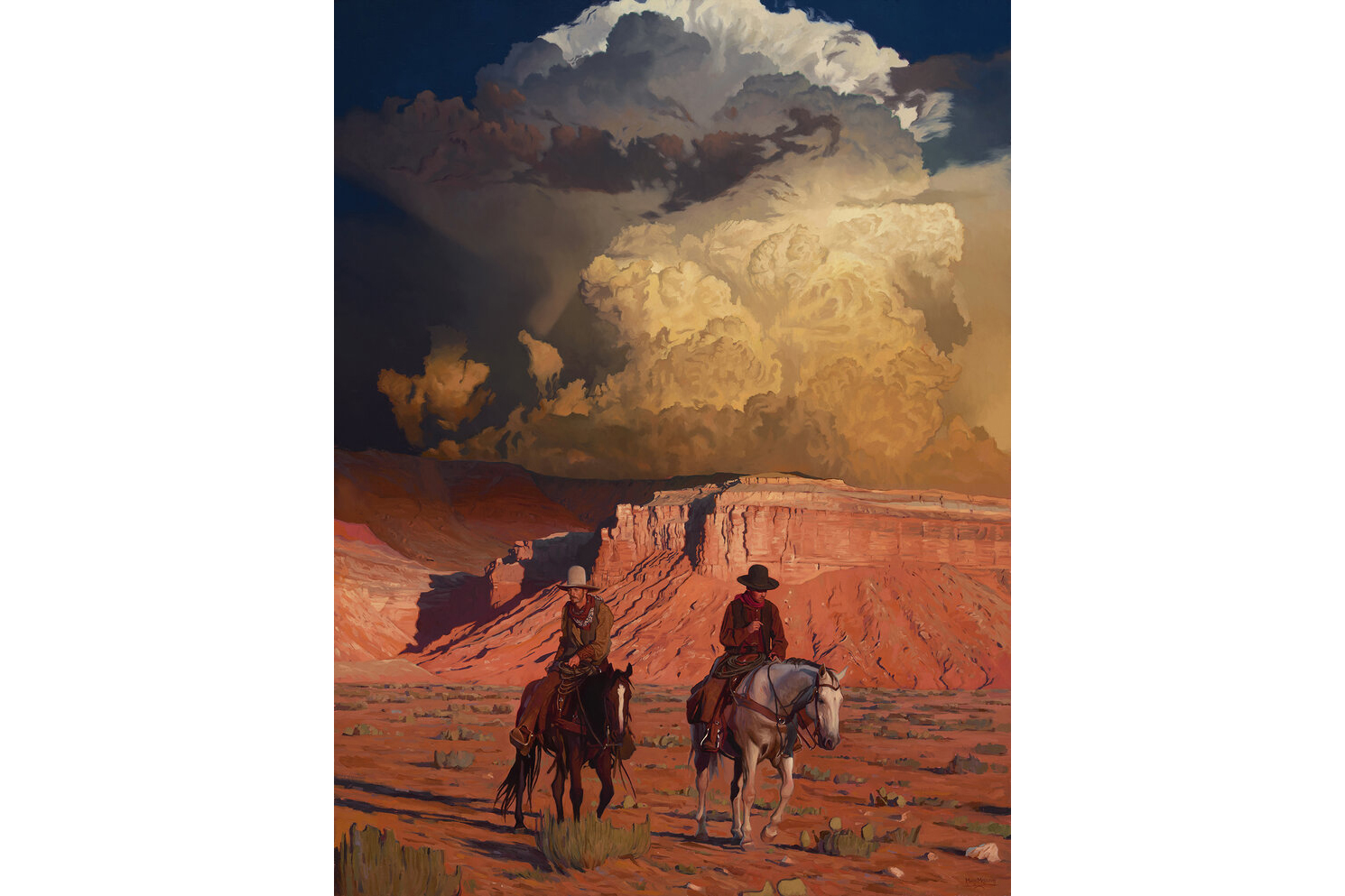

From Fontainebleau, France, Maggiori’s work may date to centuries past, but it insists on a modern consciousness. It is nostalgic and noble and melancholy and proud, a jarring reminder to Americans of the beauty and flaws within the American experiment. But its appeal extends far beyond domestic borders, and his work is cherished by collectors around the world while his prints are hoarded by any person who feels the draw of the West, thick with its symbolism and history and tragedy.

The Mythology of The American West

“History is a gallery of pictures in which there are few originals and many copies,” wrote the late Frenchman Alexis de Tocqueville. Some of what Maggiori, 43, shapes in paint owes a debt to artists that have came before: the great Western painters of centuries past like Frederic Remington, Frank Tenney Johnson, and the Taos Society of Artists, as well as modern artists like Logan Maxwell Hagege, who gave Maggiori an early break and wide exposure. But Maggiori’s work is too fresh and captures too many eyes from around the world to be solely derivative. “He has an aesthetic we all deeply crave,” says Nikki Lane, an outlaw country music star and a self-described “huge fan” of the painter. “We all want to be on that horse in that perfect moment that’s untouchable.

“You can go out there, but you can’t go out there,” she continues. “A lot of those landscapes are only tangible through his eyes.”

“Western art is the mythology of the American West and America itself,” says Michael Clawson, executive editor for International Artist Publishing and a writer who has profiled Maggiori for Western Art Collector many times. “It speaks to a lot of people in a lot of different ways.”

The West, as a subject, is romanticized, Clawson continues, but that’s true for many other genres. Left Bank Pigalle was glorified by the Impressionists, and like the Impressionists’ works of the subject, Western art is collected by people from around the world. “I don’t know if [the romanticized West] is a bad thing,” he says. “The West is romanticized. Just go out and look at it.”

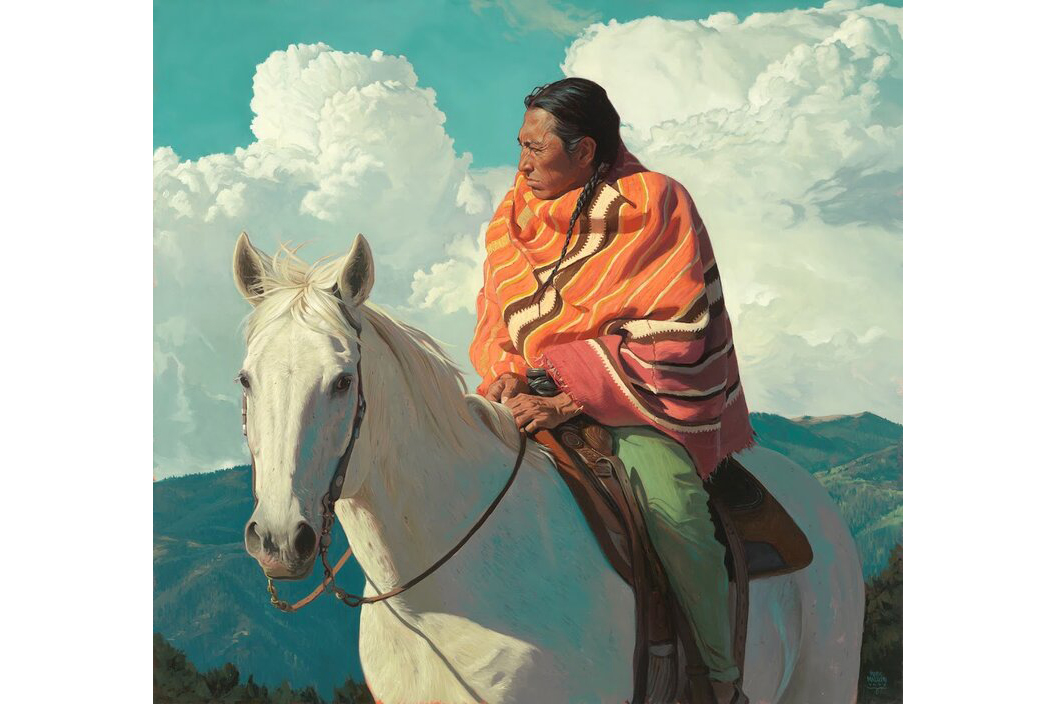

Rather than café scenes, Maggiori captures the dynamism of the quiet expanse. A cowboy paused on the rim of a canyon. A Native American looking out over a sea of sage. A buffalo soldier’s dark skin bronzed in golden hour. And over all of it, riotous, bleeding clouds as violent in their projection as Monet’s sunsets are soft and pastel. “You hear it over and over again: ‘Maggiori clouds,’” Clawson says.

“When I paint a pueblo Native at sunset, this happened, too,” Maggiori says, agreed with the idealized nature of his work. “There were beautiful moments in the history, and there was romance to it, because it was a beautiful land and there were no fences.”

New Mexico’s Influence

In April 2020, Maggiori, with his wife, artist Petecia Le Fawnhawk, and daughter, moved from his longtime home of Los Angeles to Taos, N.M. It’s a small high desert town in a sparsely populated state, and yet its history goes back centuries for artists, and for the Native Americans in nearby pueblos, millennia. “I like it better,” Maggiori says. “It’s closer to the subject matter.”

In a custom-designed studio with heated floors, Maggiori spends his days painting barefoot. “Just the light of Taos is positive,” he says, echoing an observation of artists for generations. In his new home, there’s room to explore, to experiment. His rocket ship of a career was limiting in some ways: “That’s what [patrons] wanted, so you just paint what you’ve been doing, and you turn around five years later, and you’re painting that thing over and over.” In Taos, his hand loosens with time and creativity. He feels his painting growing richer. “As soon as [past artists] went to Taos, their work just blossomed,” Clawson says. “So the fact that he’s in Taos, you can see some of the puzzle pieces coming together.”

How Art Led To Fashion

With freedom has come exploration into completely different project, and in the same year as his move, Maggiori and Le Fawnhawk launched People of the Valley, a boutique vintage shop that acts as an outlet for some of the pairs’ most cherished vintage finds that they’re ready to let go. He contributes to buying for and selling to the shop, and he and his wife together go on buying trips, but Maggiori’s focus remains on painting. “I’m involved but not involved,” he says. “I was always collecting clothing. I’ve always loved clothes.”

Nikki Lane, a successful musician who launched her own high-end vintage boutique, High Class Hillbilly, in Nashville, Tenn., in 2012, sees the parallels. “My store has become a tangible form of expression of all of the thoughts that roll through the mind,” she says. With Lane, her clothing is part of her brand, and she sees the same with People of the Valley’s offerings, from perfectly worn-in hats and distressed, stained jackets. “There’s a common thread through every piece that they pick up,” she says. “It’s shown there on the cowboy riding through the West.”

Maggiori’s Distinct Style

For as much as Maggiori may be highlighting a bygone era in his painting and his own individual fashion sense, what speaks to collectors and fans is the living, beating now-ness of it. Clawson, who was on a trail ride in August, remarks on how similar a setting, down to the very characters and attire, it was. “You can see Mark’s paintings alive and well out in the Texas Panhandle right now,” he says. “He’s painting the Old West but it resonates with the New West.”

Recently, Maggiori was allowed into the photographic archives of the Taos Society of Artists. These negatives, taking in the early 20th century, were used as the source material for later paintings, and they offer a unique glimpse into the bygone pueblo life of Native Americans. He’s also been spending time reading about their history and talking with the people themselves. “I’m trying to understand their culture before [white settlers] got here and how this whole thing ended up in a s—storm,” he says. “It’s vast, but it’s fascinating.” Of the more than 11,000 photos, he selected 100, and via his Instagram, he’s been trickling out ongoing work from them, which he says will make up a fall show, profits of which will help finance children’s programs on the pueblo. He’s also been in communication with tribal leaders of the Chiricahua Apache Nation to paint some of its members in traditional wear. While he’s wearing Westernwear every day, of late, he’s fostered an interest in Navajo textiles. “That’s trouble, because it’s really expensive,” he says, laughing.

Asking if Maggiori’s work is historically accurate is asking the wrong question, but let’s ask it anyway. The clothing of the cowboys, the tack of the horses, it all checks out. And the settings and sunsets, says Clawson, are cut right from his backyard. But Maggiori’s diverse characters and the glory of the scenes themselves skew toward artistic interpretation. Maggiori doesn’t deny it. “There’s what I know about history, and there’s what my eyes want to see,” he says. “We don’t want to cry on the past forever. We have to be constructive and build a future now.”