For many athletes, the Olympics are everything, a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to gain recognition in an obscure sport on an international stage. But that’s not true for skateboarding. Though it has ebbed and flowed in popularity since its invention in the 1950s, it flourishes on the fringe, more comfortable in back alleys than under spotlights, and in this left-of-center location, it spins off countless cultural movements (its luxury skatewear brands Supreme, Palace, and Dime being only the most recent examples). In fact, its rebel aesthetic seems not only out of place within Olympic pageantry but antithetical to it. Skateboarding may open to all races and creeds, but it remains the ultimate individual sport, both bigger and smaller than jingoism and international movements. All that to say, if Nyjah Huston leads the inaugural U.S. skateboarding contingent to the 2020 Tokyo Games this summer, the question is: Does Nyjah Huston need the Olympics, or do the Olympics need Nyjah Huston?

“It’s important for me because I love going out there and competing, no matter if it’s the Olympics or any other big contest,” Huston, 26, tells The Manual. “Obviously the Olympics is just taking that to a way bigger stage.”

It’s on “the stage” that Huston is most best known. Dominating pro street contests — the most important skateboarding discipline by far — over the last 10 years, he’s as close to a perfect athlete as anyone can be. Thirteen X Games gold medals are nothing to scoff at, but it’s his six Street League Skateboarding (SLS) Super Crowns that are even more significant, as the SLS’s modern contest format and philosophy of course layout have been lifted whole-cloth by the Tokyo Organizing Committee for this summer’s competition.

“If it was up to me, I would have some bigger rails out there on the course,” he says. “If anything, the stuff has been smaller the past few years than it was even 10 years ago when I started skating pro contests.”

Whether the rails have gotten smaller or Huston has just gotten bigger, he remains the most dominant competition skateboarder of his generation despite deeper rosters from nearly everywhere in the world, including the U.S. Unlike some earlier eras, skateboarding has never been more global and diverse than right now, irrespective of the Olympics. There are more American Black pros and amateurs than ever (Huston himself was born to a white mother and a Black father), and at the Tokyo Olympics, he will will face legitimate challenges from athletes who harken from countries in Asia, South America, Africa, and Europe — and that’s if one of his fellow Americans doesn’t take him down first. Still, Huston is the presumptive gold-medal favorite as arguably skateboarding’s greatest competitor ever and at the peak of his powers. But does an Olympic medal add much to what he’s already got?

In short, it might.

The reality is that skateboarding’s never-ending cache of cool is just too damn valuable to outside influences. In the late-’90s, when it was rising out of a near-decade-long depression, much was said about the potential corruption that would come if companies like Nike were allowed to plant their flags. “Don’t Do It” was screened onto stickers by one skateboard company, advertised prominently in the pages of Thrasher. But that company has faded into obscurity while Nike, after several fits and starts, has become firmly entrenched in the industry, poaching some of its past greats and brightest modern stars alike, including Huston. If there was a war waged, it was one of attrition, and many skater-owned companies weren’t supplied well enough to withstand a prolonged siege.

Related Guides

It’s a match predestined, then, because the Olympics are built around a corporate model. Coke, McDonald’s, and a host of other multi-national companies pay millions of dollars (little of which goes to athletes, it should be noted) to receive prime placement within and without venues and screened across the chests of its humble athletes. The International Olympic Committee may call itself representative of a global movement, but it’s more often the producer of a product, and its intellectual property is protected via the infamous Rule 40, which prohibits athletes and companies (unless paid for by said company) to use athletes’ “person, name, picture, or sports performances to be used for advertising purposes during the Olympic Games,” though the period extends for a week prior to this Games and two days beyond.

Navigating its draconian rules and penchant for litigation (see this handy guide) can be prohibitive for small-time athletes whose diminutive sponsors may not be valued at the amount it would take to buy an Olympic ad. But for larger companies — and for larger athletes like Huston himself, who, along with Team USA, is sponsored by Nike — it can work out pretty well, further expanding an individual’s brand to an audience otherwise unfamiliar with a niche sport. (One has to look no further than the amphibian Michael Phelps as proof). This, more than a confluence of nations, is the Olympic model.

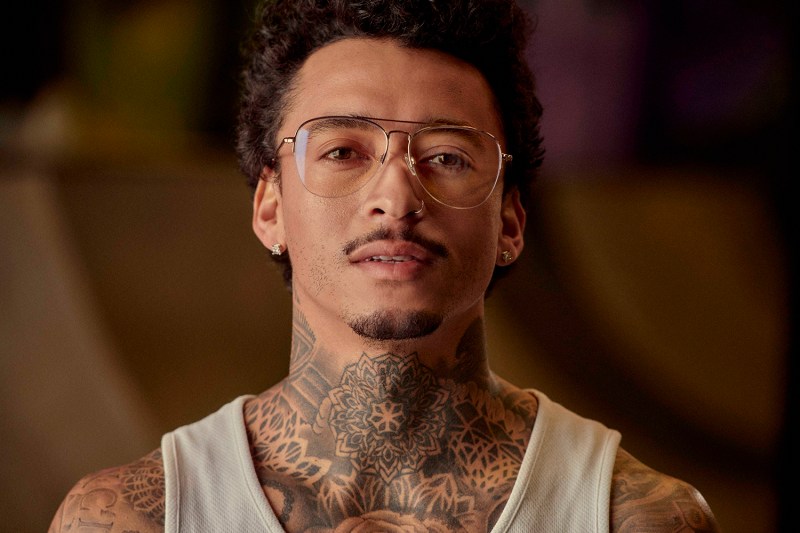

The mainstreaming of skateboarding has been nothing but profitable for Huston, who’s risen with its tide. Skateboarding’s increased prominence, arguably brought about by its bigger corporate sponsors who have bought into Huston and his success, has made the athlete the highest-paid professional skateboarder by far. He owns a private skatepark, maintains a stable of luxury cars, and announces collaborations, or short-term sponsorships, regularly, the latest of which is with Privé Revaux. The eyeglasses company worked with Huston to release a collection of three frame styles, two of which are available with the standard shade lens or blue-light-blocking glasses. “I’ve never had a whole sunglass line for myself,” Huston says, a bit of awe still in his voice at the evidence of his sport’s growing affluence. He adds that he plans to continue releases with the company over the next few years.

It should come as no surprise, then, that Huston’s apex is not without criticism within the industry. His cars, swank Los Angeles home, and frequent accompaniment by beautiful women are viewed by some as antithetical to skateboarding’s punk roots. Thrasher, the sport’s equivalent to the New York Times, has not yet awarded him its prestigious Skater of the Year title despite his longterm dominance in the contest scene. (One of Huston’s 2021 USA Skateboarding National Teammates, Jamie Foy, was the magazine’s 2017 SOTY, though few outside of core skateboarders may even know his name.)

If all this seems like intrasport nonsense, you might be right. Huston, in his conversation with The Manual, just wants to win. Sure, representing one’s country is nice, but he just wants to win. Sure, a sunglass sponsorship is great, but he wants to win. Even the possibility of no audience at the Tokyo Games — a very real threat, as fans from outside Japan have already been barred — is concerning only when it comes to winning.

“I feed off that [crowd] energy — I feel like everyone does when it comes down to those high-pressure, end-of-the-contest moments,” he says. “But if you watch me when I’m out there, I’m pretty good channeling those nerves and pressure into just hyping myself up. I put my AirPods in and not think about what’s going on too much.”

Should Huston be named to Team USA Tokyo team following the end of the qualification period in July (all but certain) and then win gold in Tokyo (likely), he will be thought of no differently within skateboarding itself. His bed, in one sense, has long been made. Before him, it was Tony Hawk, another contest skater with mass appeal to sponsors far outside the sport. But like Hawk and his X Games 900, should Huston win gold, Mainstream America may see him differently, and that would, paradoxically, help skateboarding itself.

Hawk, while openly criticized in his early contest-winning days, took his sponsors’ money and built a skateboard empire, which has since funded many far-from-the-mainstream athletes. Huston himself says he’s starting his own board company in a month or two, which would likely draw funds from all the endorsements that have drawn criticism. “More and more,” he says, he’s exploring business rather than athlete opportunities. The circle only has one side.

Someday soon, you may see Huston holding a Subway sandwich or talking into the camera for a Lincoln ad. He may tell your mother about arthritis medication or host a Bitcoin conference. If he does, it will be because of skateboarding but through corporations and the Olympics. He is already harnessing a mainstream, international appeal that far eclipses his sport’s niche roots, which then feeds more offshoots of its long-influential subculture.

So does Nyjah Huston need the Olympics, or do the Olympics need Nyjah Huston?

It may be both.

“[Skateboarders] are very diverse and worldwide,” he says, listing countries with noteworthy scenes. Markets like Brazil, Europe, South Africa, Japan. “[The Olympics are] a totally new thing for us skaters, but I think it’s sick.”