For many, March 17th is an open call to drink all of the green beer. For some, it’s a day to gorge on corned beef and cabbage. For others, it’s a day to don green apparel and go around pinching those who aren’t wearing the color. But not one of these activities has much to do with the actual, real traditional celebration of St. Patrick’s Day, the feast day of Ireland’s patron saint.

Of course, that disconnect is to be expected when said traditions stretch back around 1,700 years and are inspired by a man most of us know more misconceptions than accuracies. To help understand the real history of St. Patrick’s Day, and share a bit about the historical figure for which the day is named, we spoke to Dr. Sean Brennan, a professor of history at the University of Scranton.

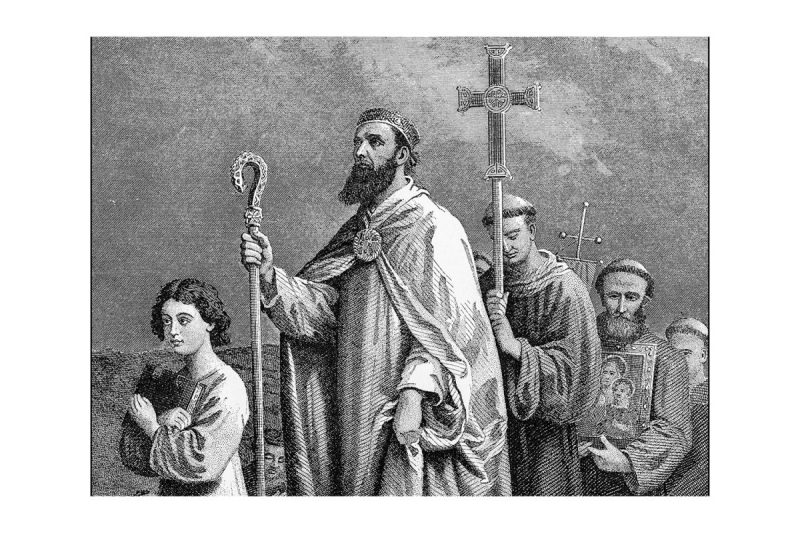

Who was Saint Patrick?

He was not Irish, that much we know for sure. “Exactly when St. Patrick was born has never been precisely determined, although most historians agree it was the late 300s or the very early 400s,” Brennan tells The Manual. He was born in Western England, likely Wales. At the time, the area was part of the Roman Empire’s province of Britannia, which consisted of both modern-day England and Wales, with its northern border marked by Hadrian’s Wall.

Related Guides

“North of the wall was what the Romans called Caledonia, what is called Scotland today, which they never tried to colonize. Neither did the Romans ever seriously try to conquer and colonize Ireland, or as they referred to it then, Hibernia,” Brennan says.

Saint Patrick was probably Roman

Patrick’s father was named Calpernius, which suggests that either he or his family was Roman by lineage. Calpernius was a deacon in the church and a minor Roman official, but during the early life of St. Patrick, Roman rule over Britain was coming to an end as the Western Roman Empire was collapsing. “At least partially due to this [instability],” Brennan says, “Patrick was kidnapped by raiders from Ireland at the age of sixteen and sold [as a] slave.”

Saint Patrick was definitely enslaved

Patrick spent six hard years enslaved while being forced to work as a shepherd before he escaped and made his way back to Britain. His time as a slave was likely spent in County Mayo, which meant he traveled 200 miles to get to the Irish coast and then back to England.

It was during this time that he embraced his Christian faith, and then, years later, he returned to his home country to spread Christianity. As Hibernia was never part of the Roman Empire, Rome’s adoption of Christianity from 313-323 A.D. completely bypassed Ireland. Most people followed a pagan religion that was based on Celtic mythology.

He had a way with the Irish

While other Christian missionaries had preached in Ireland before, none were as successful as St. Patrick in converting the Irish to Christianity. The secret to his success? “He was famous for dealing with Pagan religious believers respectfully, and even pointing out the links with their beliefs and Christianity,” Brennan says.

How do we know these details about St. Patrick?

We have all of this information about St. Partick thanks to the man himself, actually. He wrote his own book, more or less, as well as a long letter. His tome Confessio is a sort of spiritual autobiography about his life, beliefs, and missionary work in Ireland.

Another seminal work of his was called A Letter to Corocticus, in which he explores the mistreatment of Irish Christians by Britons. Because both of these works were in Latin rather than the native Irish Gaelic language, Brennan says that St. Patrick could have also helped introduce the Latin alphabet to the Irish people. His influence knows no bounds.

His death

St Patrick is thought to have died on March 17 in 460 or 461, and, as is common with Christian saints, the day of his death became the feast day on which he is celebrated. Although he was already a legendary figure in the history of Christianity in Ireland (and to a lesser extent in Britain) by the 700s, later biographies in the 800s and 1200s popularized many of the legends about St. Patrick that we know today.

When did people start celebrating St. Patrick’s Day?

Irish Christians began to celebrate the feast day of St. Patrick as early as the late 800s or early 900s, which means St. Patty’s Day has been an event for over a thousand years. Since the feast day of St. Patrick always occurred during Lent, it became associated with preparations for Easter. “The Irish would usually attend Church services to honor their Patron saint,” Brennan says, “and in the afternoon there would be celebrations with dancing, games, and feasts, often with the traditional Irish meal of Bacon and Cabbage.”

How Has the Celebration of St. Patrick’s Day Changed Over Time?

“St. Patrick‘s Day is much like Christmas,” Brennan says. Just like Christmas, St. Patrick’s Day began as a religious holiday, but has morphed into a much more secular event, especially outside of Ireland. Celebrations of St. Patrick‘s Day in America and in Canada, beginning as far back as the 17th century, were a way for people with Irish ancestry to celebrate their heritage and their faith in the New World.

It was also in the New World where the first St. Patrick’s Day parades began, dating back to 1601 in the then-Spanish colony of St. Augustine in Florida. Another early St. Patrick’s day parade was in New York City in 1772, when Irish soldiers serving in the British Army marched to honor the late saint.

Eventually these parades led to all-day celebrations in many American cities with large Irish American populations, such as Boston, New York, Philadelphia, and especially Chicago. Think about the whole green river phenomenon there, for example.

Not just a Catholic celebration

By the mid-20th century, St. Patrick‘s Day celebrations expanded beyond Irish Catholic communities. “Today,” says Brennan, “everyone is expected to at least act Irish by wearing green and celebrating, which at times has taken the negative connotations of excessive drinking. … While it would not be accurate to say the religious background of the holiday has been forgotten, that aspect of it is only important for a minority of the celebrants.”

After all, most of the modern traditions we associate with St. Patrick’s Day – green clothes, leprechauns, and corned beef – emerged in America. In Ireland, the religious parts of the holiday, like attending mass, are much more common.

But American traditions have made their way to Ireland, as well. In the past 20 years, Ireland has marked the holiday with parades. Increasingly, St. Patrick’s Day has become a global holiday and has been celebrated in Europe and parts of Asia.

Did St. Patrick really drive all the snakes out of Ireland?

No. We are sorry to report that is a myth. “It’s another false belief, propagated by his medieval biographers, that he drove the snakes out of Ireland, with the snakes being a biblical symbol of evil going back to the book of Genesis,” Brennan says. “Most herpetologists are certain that snakes never lived in Ireland. However, a legend that may have some basis in fact was that St. Patrick used the shamrock, a plant native to Ireland, to teach his converts about the Holy Trinity, given its three leaves. This is mentioned in many of the subsequent medieval hagiographies about St. Patrick, although his own writings do not.”

That is sort of a letdown about the snakes, but fine. So, while we all get ready to find our greenest outfit and figure out parking for the day’s parade, remember that there is way more to St. Patrick’s Day history than throwing back a few Irish-themed drinks. It’s great to celebrate the holiday in the way you want, but remember the historically accurate facts about not only the day, but the man behind the holiday as well.