- 1. Modern Triumph Bonneville

- 2. Modern Triumph Bonneville

- 3. Vintage Triumph Bonneville

- 4. Vintage Triumph Bonneville

- 5. Vintage Triumph

- 6. Vintage Triumph

- 7. Vintage Triumph

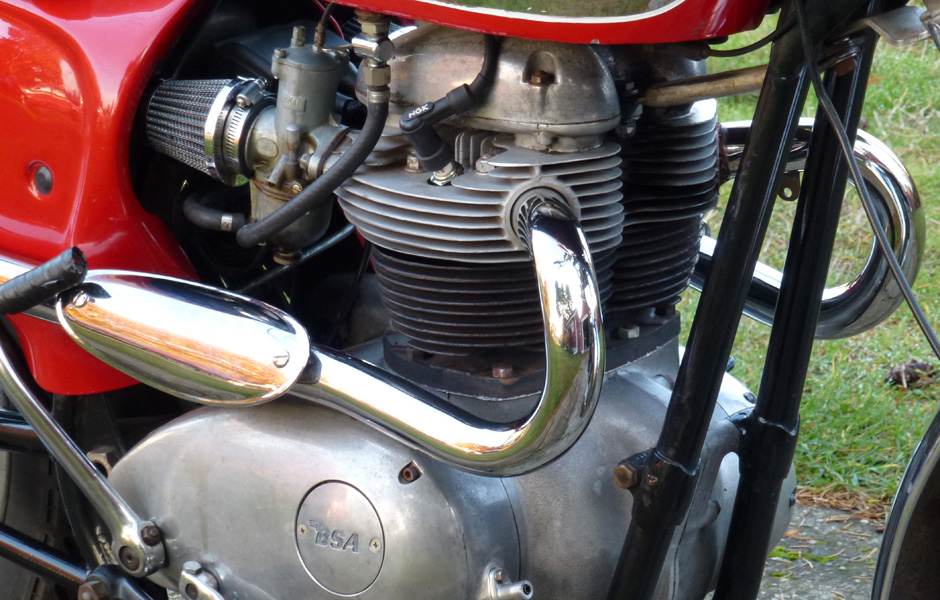

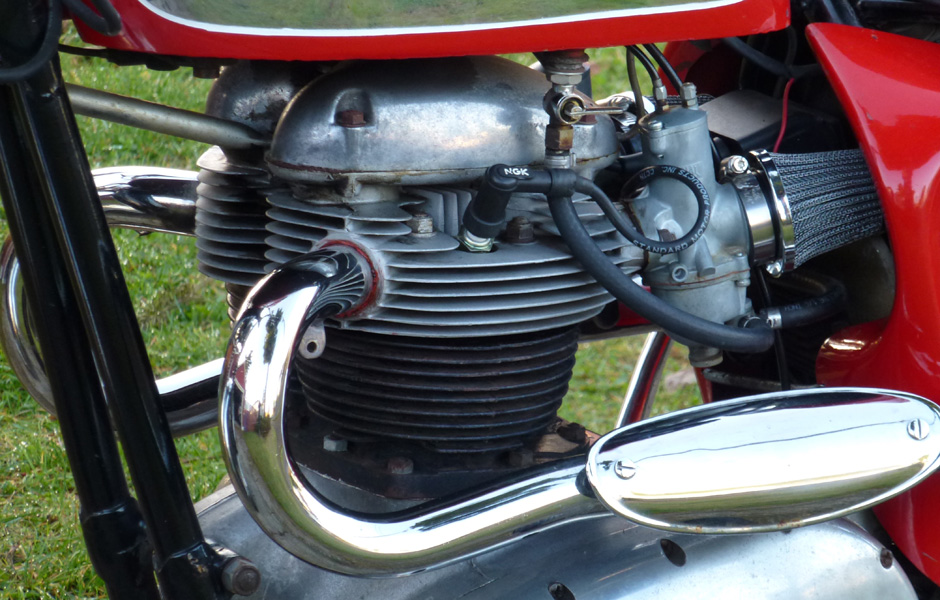

- 8. 1964 BSA A50 Hornet

- 9. 1964 BSA A50 Hornet

- 10. 1964 BSA A50 Hornet

- 11. 1964 BSA A50 Hornet

Let’s go start up my 1964 BSA A50 and go for a ride.

Pull the soft cover off the bike, roll it out of the garage and put it up on the centerstand. Click ignition switch to the “on” position on the back left sidecover (no keyed ignition here, this a former competition bike). Click on the headlight switch, check headlight (it’s on – for now). Tap rear brake to check tail light operation (it’s working – at the moment).

Open fuel petcock on right side of tank. Open fuel petcock on left side of tank. Check both for leaks (none found). Next, fish index finger to the inside part of left carburetor and repeatedly push the tiny priming plunger until gas dribbles out, scratch finger and get fuel on hand. Then repeat with right side carburetor. Go wash hands, discover child has used the last band-aid.

Return to bike, swing kickstarter out, push down slowly until compression mounts, then kick through while slightly goosing gas. Bike fires, sputters, dies. Re-prime carburetors. Skip hand washing. Kick again and again until area smells like fuel. Check spark plugs. Dry the spark plug tips. Reconsider, and install new spark plugs from pile of spare plugs in tool chest.

Rekick. Engine fires immediately, settles into a loud, lumpy idle that brings neighbors’ kids running to the windows and provokes slightly frowny face from the wife. Saddle up, put brain into British Riding Mode for shifting on the right and braking on the left, put bike in gear, let out clutch, engine dies. Consider returning BSA to garage and just riding the Honda instead.

So it goes with many a classic bike.

Properly cared for and set up, some are good as daily riders. Others, like my beautiful but terminally reluctant BSA, not so much. Back in the day (and today as well), you had to have some mechanical skills and a few tricks (and tools) in your pocket to keep an old British, Italian or American bike going. It was just part of the deal. But like the above procedure indicates (and I’m really not embellishing – much), it can also be an exercise in frustration. If only we could have classic bikes with modern convenience, right? Turns out, we can.

The starting drill outlined above and other only-for-enthusiasts peccadilloes are why Honda and the rest of Team Japan put the British bike industry out of business in the 1970s. BSA, Norton, and eventually, in 1980, Triumph – all went buh bye.

The push-button delight of electric start, the worry-free riding provided by oil-tight engines and the more approachable, more car-like utility of Honda and all the rest were perfectly timed. Convenience, reliability and low prices, even if the bikes weren’t visual and performance wonders at first, got people to sign on the line. At least you could get out and actually ride, rather than fettle about with a complicated starting procedure and worrying you won’t make it home lest something stop working (a fairly even money bet).

Of the classic Big Three britbike makers, only Triumph has risen again, although it could be argued Norton is also “back” but their limited output (and price) puts them more in the realm of boutique bike maker rather than mass producer.

Industrialist John Bloor and the initial team dedicated to bringing Triumph back from the dead did what any savvy business team would do: they toured the production facilities in Japan to help plan a modern resurrection of the classic British brand.

As the Millennium arrived, Bloor re-launched Triumph with a slate of capable if fairly unremarkable bikes built around a common architecture. It was a smart start, and as Triumph gained traction with bikes that were, at least and at last, competitive with other international brands, the model base expanded and diversified.

Finally, in 2000, while enthusiasts held their collective breath, the new Triumph Bonneville was finally announced. At 790cc’s and with all the right classic visual cues (except for a non-traditional kink in the exhaust plumbing), the “new” Bonneville was an immediate success.

Let’s just call it what it is. Despite achieving great success and putting out ever more capable machines, the Triumph Bonneville is “the” Triumph. It’s the standard bearer. Bloor was smart to basically revive the bike in an “updated” but functional (and affordable) form rather than make it some exotic halo machine or styling exercise for collectors. The modern Triumph Bonneville is fairly basic, as was the original, but it’s also good looking, capable and reliable.

Will it win races against sport jockeys on Japanese fours or Italian Twins? Not likely. But that’s not really it’s mission. Powered by an air-cooled and now up-sized 865cc parallel twin engine (aided by a bit of oil cooling), the current Bonnie has enough grunt to put away all but the fastest of cars off the line, and long enough legs for a spirited ride to the coast or the next state. It’s not a techno wonder by any stretch, but it has fuel injection (at least it does now – early models had carbs) so that’s one more thing to cross off the hassle list.

But best of all, it has The Look and if you pop for some less restrictive pipes (highly recommended), it’s got The Sound as well. It’s bulkier and bigger than its spindlier grandparents, but so are we, so that works out just fine. You sit up straight to ride it, and the flat seat is still one of the best perches for watching the scenery go by. It’s also available in a variety of flavors now, from the basic Bonnie/T100 to the urban-warrior Scrambler to the cafe-correct Thruxton. Pick your favorite.

I’ve been lucky enough to ride Bonnevilles from both eras. The 1966 Bonneville I rode, while a bit small for me, was still pretty much sex on wheels, and while sitting at a stoplight, the engine vibration was strong enough to blur your vision. The 2012 T100 version (basically a slightly gussied-up version of the base model) retained just enough of that primal vibe but included much more power, dependable electrics, modern suspension and brakes that actually stopped it in a reasonable distance. And it also had an oil-tight motor, the magic button and enough sex appeal to get a certain bike-wary spouse to ask for a ride (rare, that). Thanks, Mr. Bloor.

So there it is: the modern classic, ready to ride when you are, no dribbly carb tricks or plug swaps required. Technology, when properly married to a classic form factor, can be a wonderful, capable and stylish thing.

Anyone want to buy a nice 1964 BSA A50 Competition Hornet? It runs good – you know, most of the time.

BSA and blue/white Triumph photos by Bill Roberson

Modern and vintage Triumph photos courtesy of Wikimedia Commons