Sherry, for those in the know, is absolutely wonderful. More often than not, though, it still draws a wince from the casual restaurant or bar-goer (another fortified wine, port, knows how it feels). The stereotypes — cheap, used only for cooking, only consumed by old people — are pervasive, much to sherry’s discredit. It’s time to change all that.

The last several years have seen beer become more like wine and wine become more oxidative (e.g. natural wine styles, Jura Chardonnay, skin-fermented or orange wines, etc.). Sherry has held a certain esteem throughout, wearing its nutty, briny, dried fruit flavors on its shimmering gold sleeves and for good reason — the sherry designation contains some of the driest as well as the sweetest wines on the planet. No matter what sort of wine you are looking for, chances are you can find something similar to it within the category.

It has maintained at least a couple of small lines on most restaurant bar menus, especially as a post-meal sipper. In soccer-speak, dessert wines like port and Sauternes play the role of the quintessential number nine, scoring goals and basking in fame. Sherry wears the number 10, showing artistic flare, and it’s just as happy to deliver assist after crafty assist, even though it can easily take the place of number nine.

What is sherry?

Born in Spain and made primarily from the Palomino grape, then fortified with grape brandy, sherry goes back a few thousand years but really gained a European footing in the 13th century. Columbus traveled to the New Word with plenty in tow. Shakespeare loved it. Magellan, in what is one of my favorite drinks legends ever, is said to have shelled out more on sherry than arms as he prepared to sail around the globe.

Today, sherry, just as with other spirits or liquors, can only be made within a specific region. Known as the marco de Jerez or “Sherry Triangle,” sherry is made in three towns in Southern Spain — Jerez de la Frontera (known simply as Jerez, and pronounced “he-ref”), Sanlúcar de Barrameda, and El Puerto de Santa Maria.

Built around vulnerable grape vines, Sherry has withstood its share of disease problems. A massive phylloxera outbreak in 1894 caused significant damage to the area. It has since mostly recovered and is largely made up of four major dry types, two sweet types, and a variety of blended sherries. The four major dry types are Fino and Manzanilla, Amontillado, Palo Cortado, and Oloroso. The two sweet types are Pedro Ximenez and Moscatel, which are both named after the varietals used to produce them. We will be focusing on the dry sherries for the remainder of the article.

The production of the dry sherries — which are the bulk of all sherries produced — runs along a spectrum, from completely biological (that is, aged under the flor) to completely oxidative (aged without the flor).

The main types of dry sherry

Fino

The Fino style is perhaps the most straightforward and dry and often hit with some bread-y notes. Makes sense, given that this style is aged under the flor — barrel-aged under a film of its own yeast. There is oxygen exposure, but the perfect amount, given the flor’s protective abilities. Relatively simple and great chilled, this is a good, inexpensive introduction to sherry. Try it with tapas. Fino sherries are purely biological in their production (as are the next group, manzanilla sherries.)

Manzanilla

Manzanilla is also aged under the flor and shares many characteristics with fino sherries, except for one: Manzanilla sherry is only made in Sanlúcar de Barrameda.

Amontillado

Amontillado is a bit darker, aged in barrels under the flor (until all the flor dies), and then cask-aged and exposed to more oxygen. The result is a beautiful tawny specimen, often tasting woodsy, with candied fruit and nut elements. Amontillado sherries retain both the biologic and oxidative elements of sherry production. Try it with grilled mushrooms or artichokes and a reading from Edgar Allen Poe.

Palo Cortado

Palo Cortado is a style of sherry that functions as the best of both worlds. Aged under the flor for a little while, it is also aged oxidatively. If you can’t decide which side of the spectrum you like more, palo cortado is for you. Not as rich as oloroso, palo cortados still maintain a very full mouthfeel in each sip.

Oloroso

The darkest and most complex is oloroso, aged the longest and worthy of aging much longer (it is also not aged under the flor at all). Because it rests in cask the longest, it concentrates the most in terms of flavor. If you’re looking for sherry at its most dense and sophisticated, this style is for you.

The best sherry to try today

- The Tio Pepe Palomino Fino is the gold standard for fino sherries. Dry and crisp, it goes down easy on its own or mixed into a cocktail.

- The Hidalgo Pasada Manzanilla should be enjoyed on its own. It’s a carefully blended sherry, showing apple, citrus blossom, and roasted nut flavors. Try it out on your friends as an aperitif before your next dinner gathering.

- The Valdespino Amontillado Tío Diego is quite dry, with notes of hazelnut, dried fruit, coffee, and a hint of caramel. A well-balanced acidity makes it perfect to sip on after a meal.

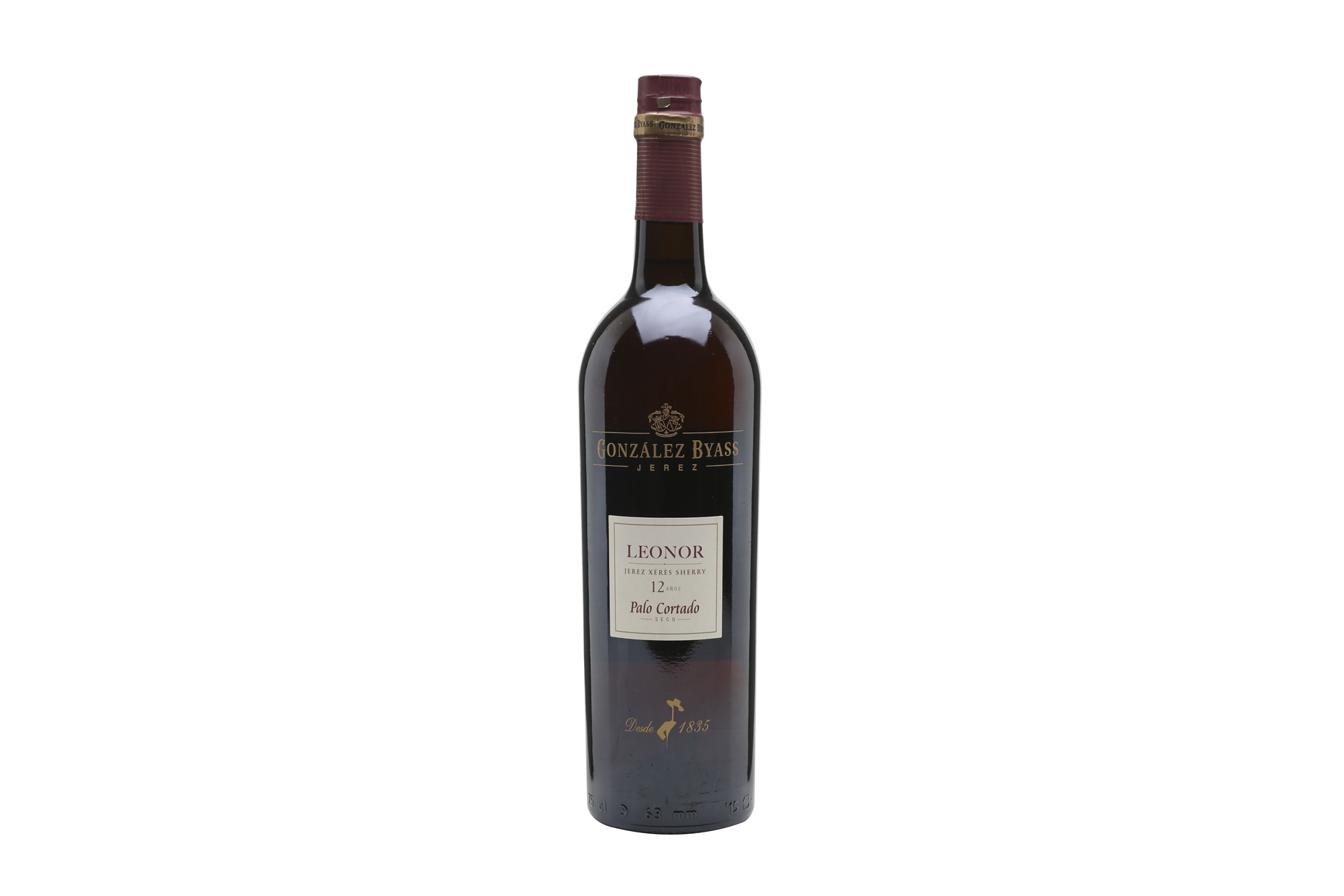

- The González Byass Leonor Palo Cortado is aged for 12 years, and is rich in nutty flavors mixed with cherries and just a little candied orange zest. Sweet on the palate, it dries slightly over time.

- The Fernando de Castilla Oloroso is built for the waning days of winter. Sip this layered sherry in front of the fireplace with a good book in hand. If you don’t have a fireplace, the warming nature of the fortified wine itself will suffice.

Bodegas Lustau is also a great brand to look up if you’re looking to dabble in the sherry circuit. If you’re feeling extra inventive, do as they do at the excellent Portland bar Rum Club and replicate their “Fino Countdown” cocktail (Fino sherry, Blackstrap, and Jamaican rums, vanilla, allspice, lemon). It’s a delightful palate bender; sweet, savory and citrusy. Need something lighter? Tio Pepe recommends a Tiojito — one part Tio Pepe Fino to three parts lemon-lime soda.

How does sherry differ from port?

Essentially, it’s all about location and the grapes used. Port largely comes from Portugal (in fact, the Porto name can only be used for offerings out of that area), while sherry comes from elsewhere (and originated in Spain). There’s a spectrum of port out there ranging from light to dark and dry to sweet, although we tend to see more of the sweeter red port here in the States.

The most popular grape varieties that go into port are Touriga Nacional, Tinta Roriz, Tinta Barroca, Tinta Cão, and Touriga Franca. While both sherry and port are fortified, the difference in grape varieties, production style, and aging make them two very different animals. We encourage you to taste them side by side, preferably with a big slab of funky cheese and perhaps some savory tapas.

Still curious about these hybrid wine styles? Check out our port wine guide and our fortified wines guide. Don’t forget to use glassware that allows you to really sniff the product and rinse in between tastes.