American wine is booming, public health crisis be damned. Here in the New World, the scene is young enough that we’re still drawing our maps, outlining certain viticultural zones, and relishing their unique climates and resulting flavors.

With so much evolution, there’s been a lot of mapping and re-mapping. Famous regions like Napa and the Willamette Valley are showing off their unique geography by way of eye-catching cartography, something longstanding locales like Burgundy and Rioja have been doing for centuries. And because we’re still figuring out just why all of these little geographic pockets are so unique, the maps are constantly changing.

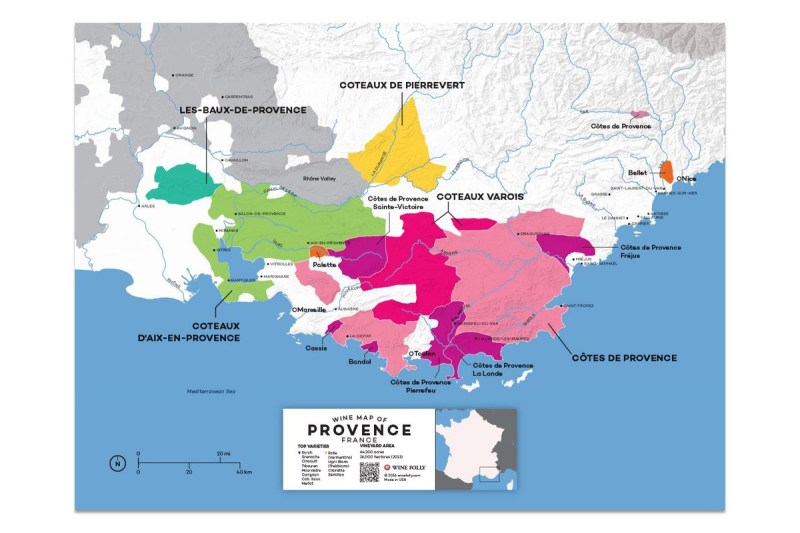

Wine Folly has been at the center of the mapmaking side of the wine boom. What started as visuals for the site’s blog in 2013 has turned into a full-grown business. Today, it’s a big part of what the brand does. It takes months to create the maps and, because the regions change so often with new appellations and boundaries sprouting up, they become irrelevant fast, too.

We chatted by email with sommelier, cofounder of Wine Folly, and mapmaker Madeline Puckette about the intersection of cartography and wine:

The Manual: What types of mapmaking projects is Wine Folly currently involved in?

Madeline Puckette: Currently, we have an ongoing project creating and updating wine maps of the world. I started with the most popular wine regions and slowly built up a collection of hundreds of shapefiles and data over time. The project started in 2013 when I made wine maps for the Wine Folly blog. The current plan is to role all of this geographic information into my partner business, Global Wine Database.

TM: Has wine country mapmaking and cartography grown with the rise of American AVAs and sub-appellations?

MP: I suspect the interest in wine maps is because of people’s reliance on and comfort with tools like Google Maps, navigation systems, iOS, etc. For me personally, I was a computer gamer and avid fantasy/sci-fi reader. Maps were a way to get a lay of the land and give context to things. Instantly.

I do not think wine maps have increased because of American AVAs. That being said, I’ve been very impressed with how new AVAs are doing a much better job using factual information (soils, aspect, elevation, climate, location) to define new wine areas. For example, the Van Duzer Corridor AVA in Oregon has clear defining features (namely wind) and a shapefile (the name for GIS area coordinates) to define it. I wish all the American AVAs were this easy to work with!

TM: What’s the biggest challenge of documenting such an ever-changing industry?

MP: Being accurate and getting good information is the biggest challenge. For example, if you want to plot all the roads of Spain, what Spanish government body has the information and how do you communicate with them to get it? I wish more countries were as organized as the USGS (United States Geological Survey). We are lucky the United States supports this endeavor.

Of course, it gets a lot harder with wine regions. It can take me weeks to create and edit a map. Thus, I’m very protective of the information. Still, I make mistakes. So, we’ve created an iterative map system so that I can fix mistakes and also add new regions when they become adopted.

TM: Given the constant updates, do wine country maps have an average lifespan in terms of relevancy?

MP: Depending on the country and location, it’s about one to three years.

TM: Are there actual mapmakers at Folly at if so, what does a workday look like for that crew?

MP: I make the maps! Currently, we receive direct feedback from customers and experts on our maps which goes into a workflow. Also, I try my best to keep track of pending AVAs or new information (maps, shapefiles, or otherwise) that may change a map. It usually takes a whole day to do an update as there are a lot of steps. We’ve also hired one amazing editor who carefully slogs through every word looking for errors. It’s hard work. Fortunately, I’m very passionate about it, so sitting down for a ten-hour stint on Geographic Information Systems is fun.

TM: Are there lesser-known values to wine country cartography (helping to map and eradicate certain pests or diseases in the vineyard, for example) besides the obvious draw that they just look good framed and on a wall?

MP: For wine drinkers, it’s both valuable and fun. Say, for example, you like Burgundy Chardonnay. Well, what other areas have a similar climate that grow the same grape? You might realize that Jura (right next door) is an untapped opportunity! For wine lovers, this is an amazing way to find undiscovered gems and good value.

For the industry, it has many applications. If we can get more accurate information about vines, vineyard location, soil moisture, weather, etc. we can become better farmers and custodians of our environment. We can also better plan and anticipate threats throughout the vintage. Ultimately, we can make better wine with more accurate maps.