If you weren’t sure that the 1980s were in vogue before, there’s no doubt now that American Airlines signed a deal to purchase 20 Boom Supersonic jets. Scheduled to be rolled out by 2025, this is a return to the ultra-fast, ultra-luxury travel that Concorde promised and delivered from its 1976 founding until insolvency in 2003.

Aspiring for passenger use by 2029, this purchase gives us a hint at just one of many future transportation modes that might evolve in the next two decades. The name of the game for current and future transport will be speed and efficiency in concert with consideration for sustainable transport (most of the time). Let’s dive in to check out some of the practical and the cutting-edge transports that may be coming soon to a road or a track near you.

Self-driven cars

Duh, right? Well, the first autonomous car concept was actually almost 100 years ago as part of GM’s Futurama exhibit at the 1939 World’s Fair. And the self-driven (flying?!) car has been developing ever since.

Now that pseudo-self-driving cars are here, the Society of Automotive Engineering (SAE), has defined five levels of autonomy in driving. This ranges from cars with no driving automation at a level 0 to “full self-driving service available under all conditions” at a level 5. Most modern semi-autonomous

Some rides, like the Tesla Model S, have made the jump to Level 2. Tesla’s Autopilot, for example, includes all features of Level 1 cars, and tacks on an optional “Full Self-Driving” package to offer lane change assistance, highway navigation, and self-parking. There’s also the opportunity to hail your Model S from the parking lot to the front entrance.

While Level 2 still requires the driver to stay in control of the vehicle, levels 3, 4, and 5 will allow for fully autonomous car control, although levels three and four make exceptions. These top three tiers will take some time to appear commercially, but you can bet your bottom dollar auto companies are hard at work to be the first to get these autonomous vehicles on the road.

Maglev trains

Improving automobile gas consumption and user function is critical to future transportation, but if we are truly going to sustain ourselves as a species, it’s trains that are going to have to connect us. It’s not apparent in the U.S., but North America is lagging way behind its brethren in Asia and Europe when it comes to futuristic travel. Exhibit #1? Maglev trains.

Magnetic levitation (mag-lev, get it?) from powerful electromagnets pushes these trains forward along electrified guideways. A lack of friction allows these trains to travel at high speed with considerably less noise and a smoother ride than traditional track trains. It’s an understatement to say that these trains are “high speed” when they’re able to reach speeds at least half as fast as jets. A maglev bullet train that debuted in Qindao, China, for example, can reach speeds of 373 miles per hour. Developed by the state-owned China Railway Rolling Stock Corporation, this maglev is considered the world’s fastest train.

Britannica lists six commercial maglev systems currently in operation — one in Japan, two in South Korea, and three in China. Because these super lines are not powered by burning fossil fuels, they are magnitudes less impactful on the environment. The first U.S. maglev train is still in development, in partnership with a Japanese firm, with plans to connect Washington D.C. and Baltimore and, eventually, New York City.

Delivery drones

It may seem like drones just appeared on the scene in the last 10 years, but the first automatized flying machine actually appeared in 1935. The history of unmanned aerial vehicles goes back to providing bogies as aerial practice targets for Royal Air Force fighter pilots. This began by towing gliders behind crewed aircraft. When this failed to provide a realistic simulation for engaging enemy fighters in live combat, the RAF developed the Queen Bee aircraft — a radio-controlled drone.

The following year, U.S. Admiral William Harrison Standley put Lieutenant Commander Delmar Fahrney in charge of developing a similar program after seeing a UK test flight in 1936. Fahrney first used the term “drone” as a sly nod to the Queen Bee.

Eight decades later, the first UPS drone delivered prescription medications to U.S. homes in 2019. Drones still have a long regulatory path to tow, however, before the flying machines are rolled out for full-scale commercial use. At present, delivery is limited to rural areas and hospital campuses because drones pose a risk to life and property. Each U.S. state is working with the FAA to develop drone testing, restrictions, and regulations.

Hyperloop

Now we get to start to have a little fun with future visions. Imagine strapping not into a train, but into a glass tube that, upon closing its doors, whisks you across the Earth at almost the speed of sound. Welcome to the hyperloop.

Elon Musk is credited with conceiving the modern idea of the hyperloop, first broaching the idea of a high-speed system in 2012, and, in 2013, published a white paper with plans for a Los Angeles-to-San Francisco super tube. This was an update of a two-hundred-year-old idea, suggested first in 1799 when English inventor George Medhurst patented a system of iron pipes that used compressed air to propel goods through pneumatic tubes.

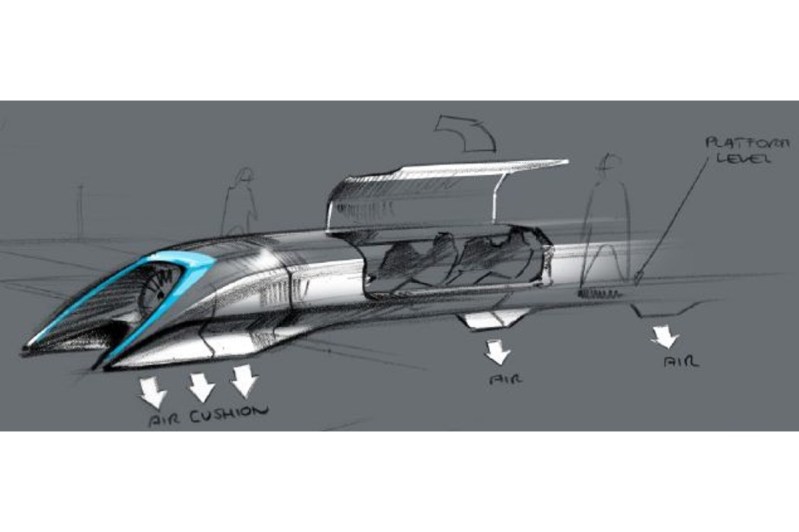

Musk’s hyperloop proposed pressurized pods that could carry up to 28 people and shoot them through a system of glass tubes powered, in part, by vacuum, and generating speeds of up to 600 miles per hour on skis hovering on an air cushion. Though the open source design has only achieved what amounts to a theme ride so far in Las Vegas, there are a multitude of companies and countries building hyperloop prototypes.

With an expected date of arrival around 2030, India and Middle Eastern nations are deep into advancing technology that could move freight cheaper and more efficiently from place to place via hyperloop.

The Virgin Hyperloop, being developed in Nevada, aspires for a number of routes through the U.S. carrying passengers with 10 times less energy than jets and traveling at “500 miles per hour for less energy (per passenger) than an electric car doing 60 miles per hour.”

Flying taxis

Yep, flying taxis. Imagine zooming up above traffic and hopping a ride over interminable gridlock via electric-powered propellers. Over 20 companies and dozens of the world’s best engineers are putting their effort into making flying taxis a reality.

Earlier in August, The Wall Street Journal reported that United Airlines Holdings Inc. put down a $10 million deposit for 100 electric flying taxis with Archer Aviation Inc. This is one of many signs that the nascent technology is very much in vogue, especially among already established air companies.

As of 2021, at least 14 flying cabs and cars were in development. The biggest hurdle, of course, is regulation. It’s going to be quite a tightrope walk to balance FAA requirements with local zoning ordinances to get these electric crafts into commercial use. The aim is that air taxis would provide safe, inexpensive, and greener rides than sitting in traffic. With volocopters and self-driven planes on the horizon, it may not be long before we’re able to air hop home from the airport.

Above price and safety pressures, the biggest challenge will be the ambition and collaborative spirit to achieve these transportation visions. In the twentieth century, the U.S. helped to bring private auto use, commercial flight, industrial agriculture, and much more to the world. Along the way, inventors turned into oligarchs, setting obstacles in the way of competition, or just outright destroying competitors as car companies did with mass transit systems in Detroit, L.A., and more.

Many of these ideas have been around for decades, if not centuries. Now that we are on the cusp of creating a system of sustainable, efficient ways to move people and things around and off the planet, it remains to be seen if humanity is able to harness these powers in an enduring, equitable manner.